Looking back at 2022 and 2023

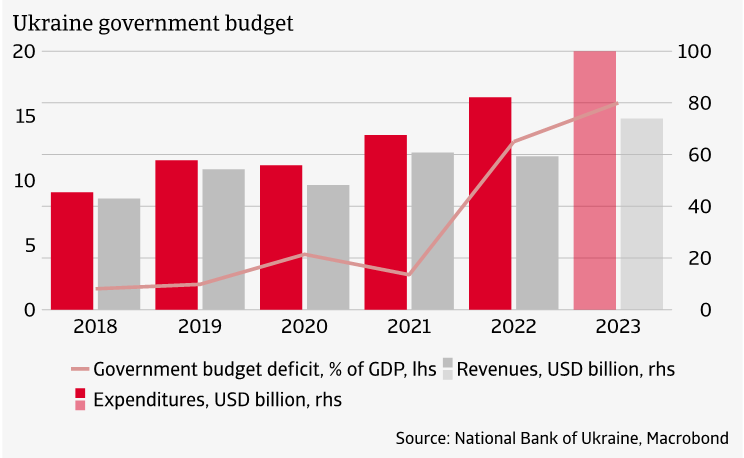

The war has dealt a major blow to Ukraine’s economy and government finances. In 2022, GDP contracted by around 30%, followed by a limited 3.4% recovery in 2023. Inflation also increased rapidly as a result of the depreciation of the hryvnia and the rise in commodity prices. Total government expenditure increased from USD 68 billion in 2021 to USD 100 billion in 2023. Revenues also increased, but not enough to compensate for higher expenditures. The difference between expenditures and revenue is the budget deficit, which rose from 3% of GDP in 2021 to 16% of GDP in 2023 (figure 1).

The bulk of higher government expenditures in 2022 were driven by higher defense and security spending, which increased from USD 11 billion to USD 43 billion (this represents an increase from 6% to 22% of pre-war GDP). In 2023, defense and security spending increased further to USD 63 billion. On the revenue side, tax revenues declined by 32% in 2022, from USD 53 billion in 2021 to USD 36 billion. Despite lower tax revenues, total government revenues went up because of higher grants provided by foreign governments and International Financial Institutions (IFIs). For accounting purposes, grants are recorded as government revenues.

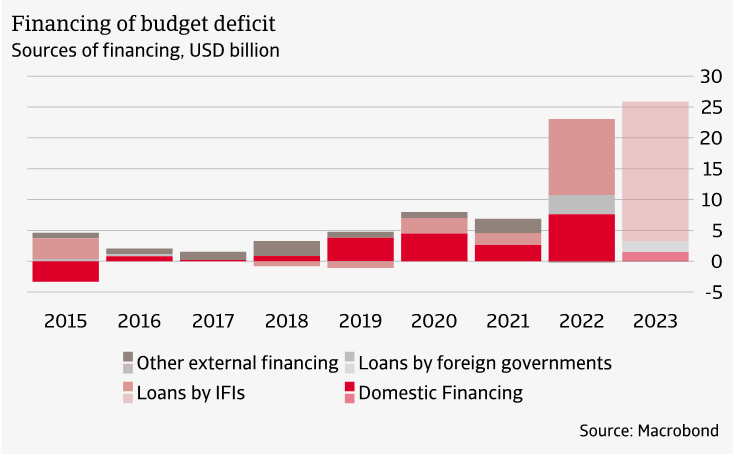

Grants, which are booked as government revenues, rose from close to zero in 2021 to USD 13 billion in 2022. In 2023, they have reached USD 11 billion (data until November 2023). Without these grants, the budget deficit would be even higher. Ukraine’s budget deficit went up from USD 7 billion in 2021 to USD 23 billion in 2022 (figure 2). The bulk of the 2022 budget deficit (USD 15 billion) was financed by external loans from foreign governments and IFIs. In 2023, loans from foreign governments went down, but the IFI loans went up considerably.

Some of the IFI loans have been provided by the IMF, with which Ukraine has had a program since March 2023. The overarching goals of the IMF programme are to ensure economic and financial stability during a period of exceptionally high uncertainty, restore debt sustainability and promote reforms.

The size of the IMF programme is USD 15.6 billion for the duration of four years. USD 3.5 billion of this has already been disbursed to Ukraine.

Besides external support, Ukraine also managed to step up domestic financing in 2022. Since February 2022, Ukraine has been able to raise USD 6 billion from the issuance of domestic war bonds, which can be bought by the general public. However, this source of financing was less successful in 2023 as figure 2 shows. Despite the fact that the government still managed to sell war bonds, it had to make principal and interest payments on outstanding war bonds, leading to an overall decline in 2023.

Most important donors

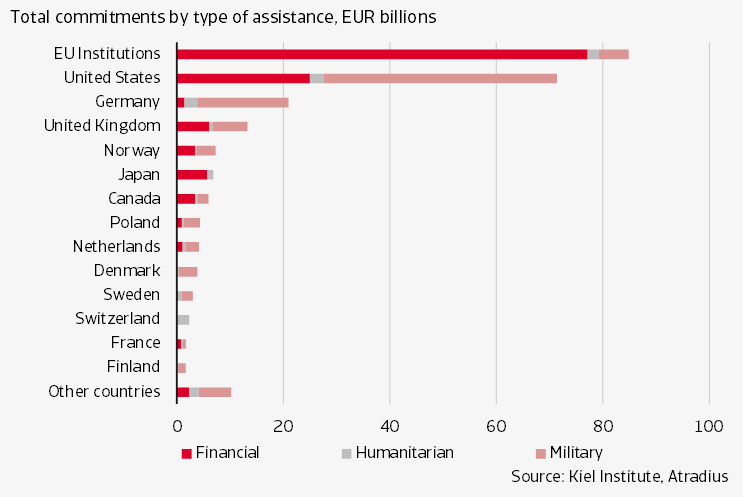

The Kiel Institute collects data on external support given to Ukraine distinguishing between three main types of assistance: military assistance, humanitarian aid and financial assistance. Financial assistance consists of grants, loans, guarantees and swap-lines. These can be short-term bilateral commitments (one year or less) or multi-year commitments. Military assistance includes all types of weapons and military equipment alongside items donated to the Ukrainian army as well as financial assistance tied for military purposes. Humanitarian aid refers to assistance supporting the civilian population (mainly food, medicines, and other relief items). In-kind support like military equipment and weapons is estimated at market prices and upper bounds of prices are used to avoid underestimating the true scale of assistance.

Since the large-scale Russian invasion in 2022, the cumulative aid pledged by the United States, the EU and other Western partners adds up to EUR 242 billion, of which EUR 128 is financial assistance, EUR 16 billion is humanitarian aid and EUR 98 is military aid. The top donors are the EU institutions and the United States, followed by several individual European countries. The composition of aid varies, however, with the US providing mostly military aid while the EU provides mostly financial assistance.

When aid is expressed as a percentage of each donor’s economic size, Lithuania (1.8% of GDP), Estonia (1.8%), Norway (1.6%), Denmark (1.6%) and Latvia (1.5%) emerge as the largest donors. These countries are followed by Slovakia, Poland, the Netherlands and Finland, each contributing more than 1% of GDP. On the same measure, the United States donates 0.3% of GDP and the United Kingdom 0.5%.

The Kiel Institute also tracks aid over time. Between August and October 2023, they recorded an almost 90 percent drop in newly committed aid compared to the same period in 2022. Ukraine now increasingly relies on a core group of donors such as the US, Germany, and the Nordic and Eastern European countries. Moreover, Ukraine can rely on the large previously pledged multi-year programs.

Two scenarios

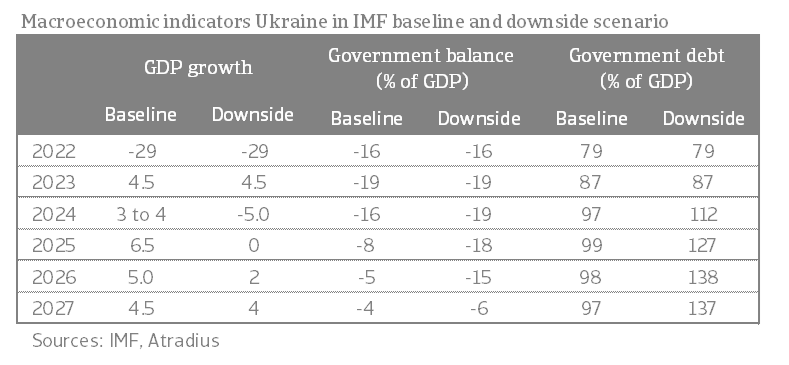

To see how Ukraine’s financing need could develop in the coming years, we look at projections that the IMF has made. The IMF has developed a baseline scenario and a downside scenario for the coming years. The baseline scenario assumes that the war between Russia and Ukraine winds down by the end of 2024. The downside scenario assumes a longer and more intense war, with hostilities to wind down by end-2025. In the downside scenario, there is greater damage to the capital stock, a slower return of migrants, and weakened balance sheets compared to the baseline scenario. This also means that the expected GDP recovery is slower in the downside scenario. In the baseline scenario the GDP recovers to its pre-war level in the early 2030s, whereas in the negative scenario this would be only by the end-2030s.

Table 1 illustrates both scenarios on some key economic indicators.

The IMF expects in its baseline scenario that the deficit will remain very high in the near term (19% in 2024), before it gradually declines as the intensity of the war becomes lower. In the downside scenario, the deficit remains above 15% for an additional two years due to higher defense spending and lower economic activity, before it starts to decline substantially. The high deficit also has implications for government debt. In the baseline scenario, it is expected to increase to almost 100% of GDP in 2025, before it gradually declines. In the downside scenario, debt peaks at 138% in 2026.

The IMF deems a debt restructuring necessary in order to make government debt sustainable. According to our calculations, the debt restructuring could involve tens of billions of USD of outstanding debt.

The most important creditors - the G7 countries plus several smaller Western countries, assembled in the ‘group of creditors’, have already promised Ukraine a debt treatment to restore debt sustainability once the situation has stabilized or at the latest by the end of the IMF programme (2027). Moreover, they have provided financing assurances and suspended loan repayments also during the IMF programme.

External support remains indispensable

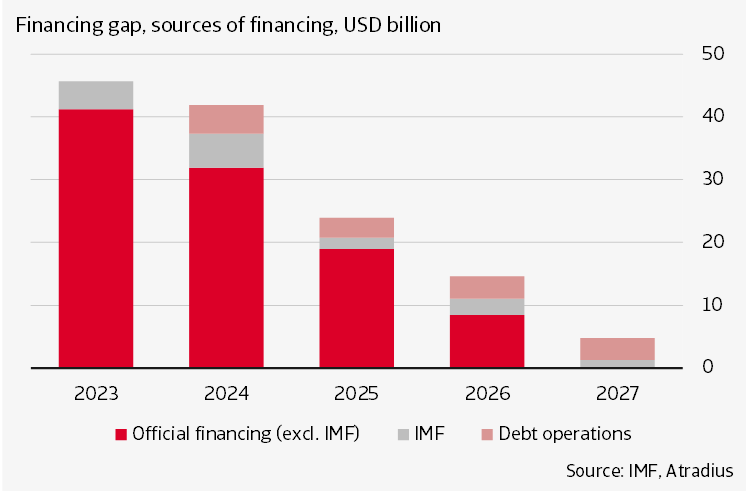

Regardless of the further course of the war, it is clear that international support remains indispensable to Ukraine. According to the IMF baseline scenario, the Ukraine government has a USD 114 billion financing gap during the programme period (2023-2027) (figure 4).

In 2024, Ukraine needs USD 37 billion in external support. For 2025, support is projected to be USD 21 billion, but after that it declines substantially. Most of the financing gap has to be covered by bilateral donors (in the figure this is part of official financing (excl. IMF).

Under the downside scenario, the financing gap could grow to USD 140 billion. The external support requirements under this scenario remain high until 2026. Under the downward scenario, the IMF assumes additional financing will be arranged, which is consistent with assurance given by the international group of creditors. Again, most of the funding has to come from international donors. A return to the international capital market is not deemed realistic during the duration of the IMF programme, but the IMF does assume a return to the capital market is possible in 2029.

In additional to the annual budgetary spending that is associated with an economy under war, there are also the long-term costs of reconstruction and recovery. These costs are estimated by the World Bank to be USD 411 billion, or 2.6 times the pre-war GDP of Ukraine. This cost estimation only covers damage incurred during the first year of the war. The most urgent needs are in restoration of energy, housing, critical and social infrastructure, basic services for the most vulnerable, explosive hazard management, and private sector development.

As this note has argued, Ukraine's financing needs will remain high in the coming years. International support is the backbone of the Ukrainian economy. In a scenario where Ukraine would be cut off from external aid, macroeconomic balances could soon spiral out of control. For example, it could force Ukraine to cover budget deficits with monetary financing, putting pressure on the hryvnia and increasing inflation. In time, it could also lead to a default of Ukraine on its foreign debt. Moreover, a sharply reduced support will also negatively affect Ukraine's military capabilities. That is why the growing reluctance among Western partners to pledge financial support to Ukraine is all the more worrying. A Trump victory in the US 2024 elections could end US support to Ukraine completely, which would put an even greater burden on the EU.

Theo Smid, Senior Economist

theo.smid@atradius.com

+31 20 553 2169

All content on this page is subject to our Disclaimer, available here.

Summary

- Since the beginning of Russia's large-scale invasion, Ukraine has been paying a high humanitarian and economic toll. The economy shrank by almost one third in 2022 and the government budget was thrown significantly out of balance.

- In 2022 and 2023, Ukraine received approximately USD 65 billion in state budget financing. Much of this has gone to increased defense and security spending. In total, about EUR 128 billion in financial aid has been pledged by international partners, including the US and the EU.

- The Ukrainian economy is expected to slowly recover in the coming years. However, the need for foreign aid will remain. The IMF assumes a government financing need of USD 114 billion in the period up to 2027. In this respect, it is worrying that new support commitments have come under pressure in recent months.

Ukraine is paying a high humanitarian and economic toll as a result of the Russian invasion on February 24, 2022. The war has displaced about 6.3 million Ukrainians, out of a pre-invasion population of 42 million. Ukraine's economy has shrunk by almost one third in 2022 due to Russia's annexation of territory from Ukraine, destruction of buildings and infrastructure, and the shrinking labour force as a result of army conscription and people becoming displaced. The future course of the war remains uncertain, but the conflict is currently at a stalemate. The most likely eventual outcome seems a ‘frozen’ conflict comparable to that between North and South Korea at the end of the Korean War (1950-1953). The latter ended with a ceasefire, but no formal peace treaty.

This research note focuses on support received by Ukraine from Western countries and international institutions such as the IMF and World Bank. In recent months, this support has come under pressure, as there seems to be a growing fatigue among Western partners. In the US, a USD 61 billion aid package for Ukraine has stranded in Congress, as Republicans are reluctant to send more money. In Europe, the EU failed to approve a USD 50 billion aid package for Ukraine as proposals were blocked by Hungary. EU leaders are now drawing up alternative plans either keep Hungary on board or to bypass Hungary. According to the Kiel Institute, there was a sharp drop in newly committed aid between August to October 2023 compared to the same period in 2022. Still, we argue that international support remains indispensable for Ukraine in the years to come.